What Do We Choose to Memorialize?

Week 12 - 11/21/2019

“Monuments don't mean things on their own. They mean things because we make them mean things. So this Robert E. Lee statue, which I suspect most Charlottesvillians would have walked past and ignored as well, has taken on a new valence. And I think that's an important reminder. Monuments are not static things that have a single narrative behind them. Monuments are things that we create. Monuments are objects whose meaning and significance we create daily.”

- Jennifer Allen, What Our Monuments (Don’t) Teach Us About Remembering the Past

Openings

What do we choose to memorialize? Who should decide what we memorialize? What constitutes a memorial? In 2013, the city of Philadelphia voted to close 23 schools for the 2013-14 school year. The schools ranged from elementary schools to high schools and were located across the city. The city cited under enrollment and budgetary restrictions as the reasons for these closures. As a result, thousands of students and teachers around the city were displaced, the buildings left abandoned, their fates unknown. In this class, we explored if and how the city of Philadelphia should memorialize these closed schools and honor the communities they once served.

Guiding Questions and Suggested Literature

Why did 23 Philadelphia schools close in 2013? How do we honor these schools’ erased histories?

Philadelphia School closures

John Rury & Shirley Hill. 2012. “An End of Innocence: African American High School Protest in the 60’s and 70’s.” History of Education.

Kristen Graham. 2017. “These Philly schoolkids marched against injustice 50 years ago, and police responded with nightsticks. Today, they inspire a new generation.” The Philadelphia Inquirer.

Notebook staff. 2013. “Saying goodbye to 24 Philadelphia Schools.” The Notebook.

Dan Stamm. 2013. “23 Philly Schools Slated to Close” NBC (video)

What do we choose to memorialize? What is the purpose of a memorial?

Monuments and memorials

Kat Chow, Leah Donella, & Gene Dembey. 2017. “What Our Monuments (Don’t) Teach Us about Remembering the Past.” NPR.

Dell Upton. 2015. “Introduction.” What Can and Can’t Be Said: Race, Uplift, and Monument Building in the Contemporary South. Yale University Press.

Who should decide what we memorialize? How should we memorialize erased histories?

Current memorial projects

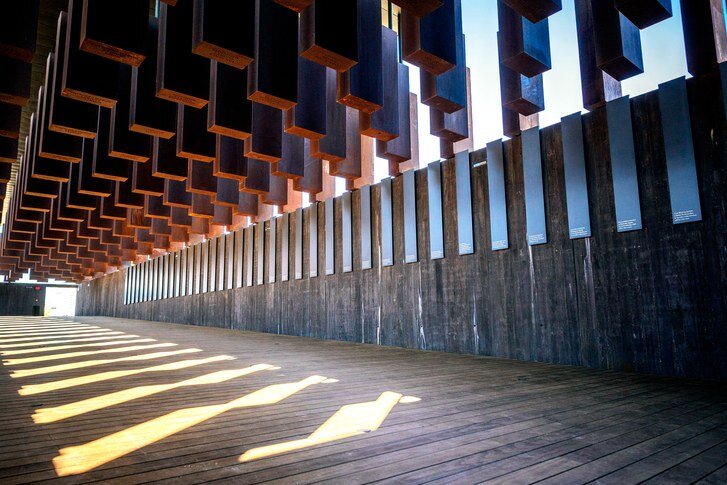

Campbell Robertson. 2018. “A Lynching Memorial is Opening. The Country Has Never Seen Anything Like It.” New York Times.

2018. “Creative Speculations for Philadelphia: Report to the City.” Monument Lab.

“Tragedy Into Hope: Students Rally to Create a Memorial for Ell Persons.” Facing History and Ourselves. (video)

Class Recap

Inspired by the activism of a group of students at Masterman High School in Philadelphia to memorialize the 1967 student walkouts in Philadelphia, we aimed to consider the significance and tensions of memorialization, more broadly. We considered what constituted a memorial in the first place; we began class by sending students to the former West Philadelphia High School (now West Lofts) and the former Bok High School (now a multipurpose co-working, living, and consumer space) to create physical and spatial memorials with our bodies through audio tours. In class, as we examined a map of all the closed schools in the city of Philadelphia, we collectively acknowledged and mourned the spatially vast consequences of these school closures. We explored what successful memorials must look like—they must be disruptive, invite engagement, be community-based—as well as key limitations when making memorials—proper allocation of resources, erasing present-day narratives and experiences, promoting mythology over action. We concluded by imaging what successful memorials for West Philadelphia and Bok High Schools could be.

Kehinde Wiley’s monument, “Rumors of War” in Times Square in New York City

Quotes from Class Notes

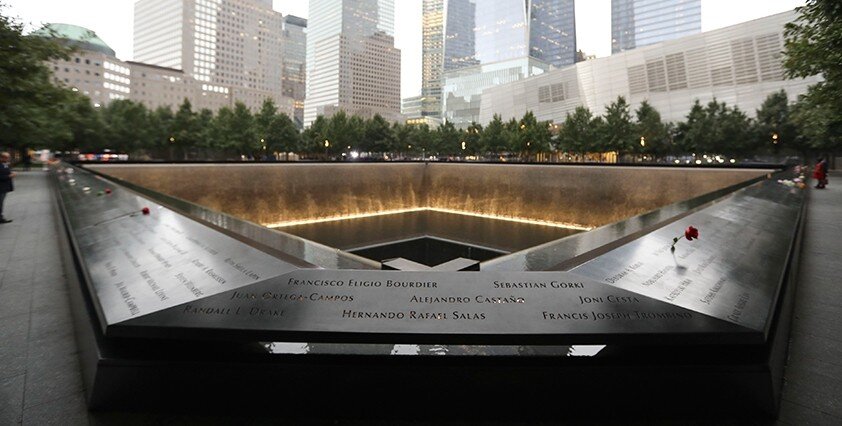

A memorial should be something that interrupts your day. It interrupts the natural flow of a landscape, a city. Something that is worth remembering happened there.

Memorials should be a forced consciousness. Something you cannot miss.

The beauty of happenstance. Is there more power in a memorial that exists outside of plain sight? That is hidden, and found only upon chance, in such a way that makes the memorable more poignant, more memorable?

Who should create memorials? Sometimes memorials are used as a PR stunt or by private entities to make money. But should the creation of memorials be the responsibility of those harmed? There is power in a state (like Germany with the Holocaust) taking accountability through memorials.

What is the difference between building a memorial for people who may no longer be in a place vs. those who still are? How can the building of a memorial participate in the erasure of a community? A memorial can suggest that what is being memorialized is something of the past, that may no longer need to be funded, no longer need resources. How can we reconcile an urge to memorialize and confer significance with a need to still support communities in need?

What about an experience do we memorialize? It’s often war and violence, those who died. We do not often memorialize the actions of youth activists. As much as brutality needs to be remembered, agency does, too. When we fetishize violence and pain, how does that erase agency? One’s entire remembered identity is about suffering, not the rest of their identity.

We should consider the intergenerational legacy of memorials. What survives?