Social Emotional Learning: A Pedagogy of Control

May 14, 2018

By Ryan Haas

“Revon, calm your body, or we’ll all start over.”

“Lemarr, you don’t earn points until you’re quiet!”

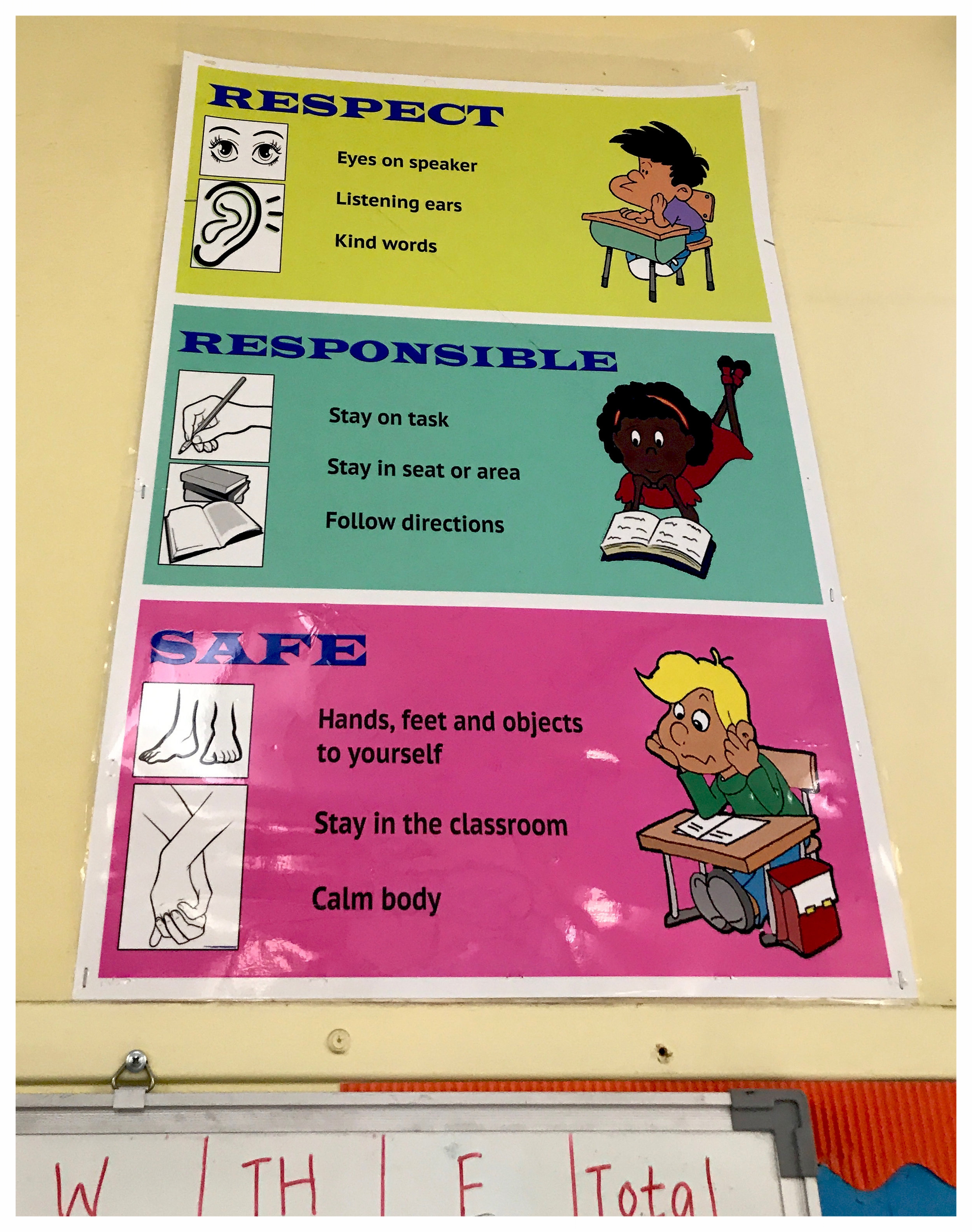

In a special education classroom, a teacher opens the morning with a mindful minute meditation. This particular classroom is on the first floor of a public elementary school nestled against a San Francisco hillside, and quarantines students labeled emotionally disturbed. Colorful posters on the wall suggest emotions, bodies, and words for kids to be ‘responsible,’ ‘respectful,’ and ‘safe.’

Down the hall, a kindergarten teacher reprimands Peter, a five-year-old boy, for saying “No!” She points to the “be respectful” poster on her wall. She tells him to take some “think time” and sends him to the corner.

One floor above, an eight-year-old waits in the hall, stomping his foot against the door. The teacher peeks outside and says, “Dauntay, I’m not going to let you in until you tell me how you’re feeling.”

In its 2016-2019 strategic plan, the San Francisco Unified School District defines social emotional learning as “the process through which we acquire and apply the knowledge, attitudes, and skills necessary to manage emotions, set and achieve goals, show empathy, maintain positive relationships, and make responsible decisions.”

I ask, whose knowledge, attitudes, and skills? Manage emotions for whom? Positive how, and to whose benefit?

I worked at an elementary school that rigorously implemented such social emotional learning (SEL) curricula. Promising safe schools, healthy children, and improved academics, the neoliberal product disguises dehumanization as intervention, surveillance as psychometrics, and punishment as learning.

Since the publication of Goleman’s Emotional Intelligence: Why it can matter more than IQ in 1995, a lucrative market for improving and empowering the child has produced research promising to prepare kids with the social-emotional skills for a 21st century world.

This literature abstracted emotion and social interaction into skills for direct instruction and academic gains. Among these skills: forgiving, naming emotions, patience, asking, apologizing, shaking hands, silence when others talk, recognizing authority, and following directions. Dr. Diane M. Hoffman, Associate Professor of Education at the University of Virginia, reviews, “SEL advocates see cause for optimism in the assumed measurability and teachability of emotional skills and competencies because presumably this means that individual performances can be measured, deficiencies can be assessed and remediated, and in the end all children can be taught the appropriate skills and behaviors.”

In doing so, SEL advocates position individuals as the site of the problem and the unit of analysis. Instead of finding ways to increase food available, teachers ask youth to manage their hunger and suppress their anger. Instead of asking why movement must be restricted, teachers assume youth need to be taught patience and stillness. Instead of examining what the teacher did to upset a youth, the focus is teaching youth to remain calm. Where administrators should be concerned with the size of a class, they assert kids just haven’t learned to manage anxiety.

The result is a systematic objectification of youth’s interactions. See, for example, this video, produced by the Swift Center for the California Department of Education, depicting best practices for “inclusive support.” This state-wide approach is steeped in behaviorism, a model of teaching and learning dating back to 1930’s and psychologist B.F. Skinner, developed on lab rats.

Drawing on the research of Dr. Frank M. Gersham, the California Department of Education recommends schools implement tiered reward-based behavior systems, evaluate how youth respond, and use that data to assign them disability. Consequently, the most resilient youth “respond” the worst. These youth deny compliance and demand respect. As SEL supports increase, youth either submit or are diagnosed “emotionally disturbed.” At Leonard Flynn Elementary, these youth were quarantined in a special day class for intensive social emotional learning control.

In its 2013-2014 report on innovation in SFUSD, Leonard Flynn Elementary lauds the program for addressing “an equity issue that has impacted the large numbers of African American and Latino students in Special Education.” The issue? African American and Latino students were not receiving enough social-emotional intervention.

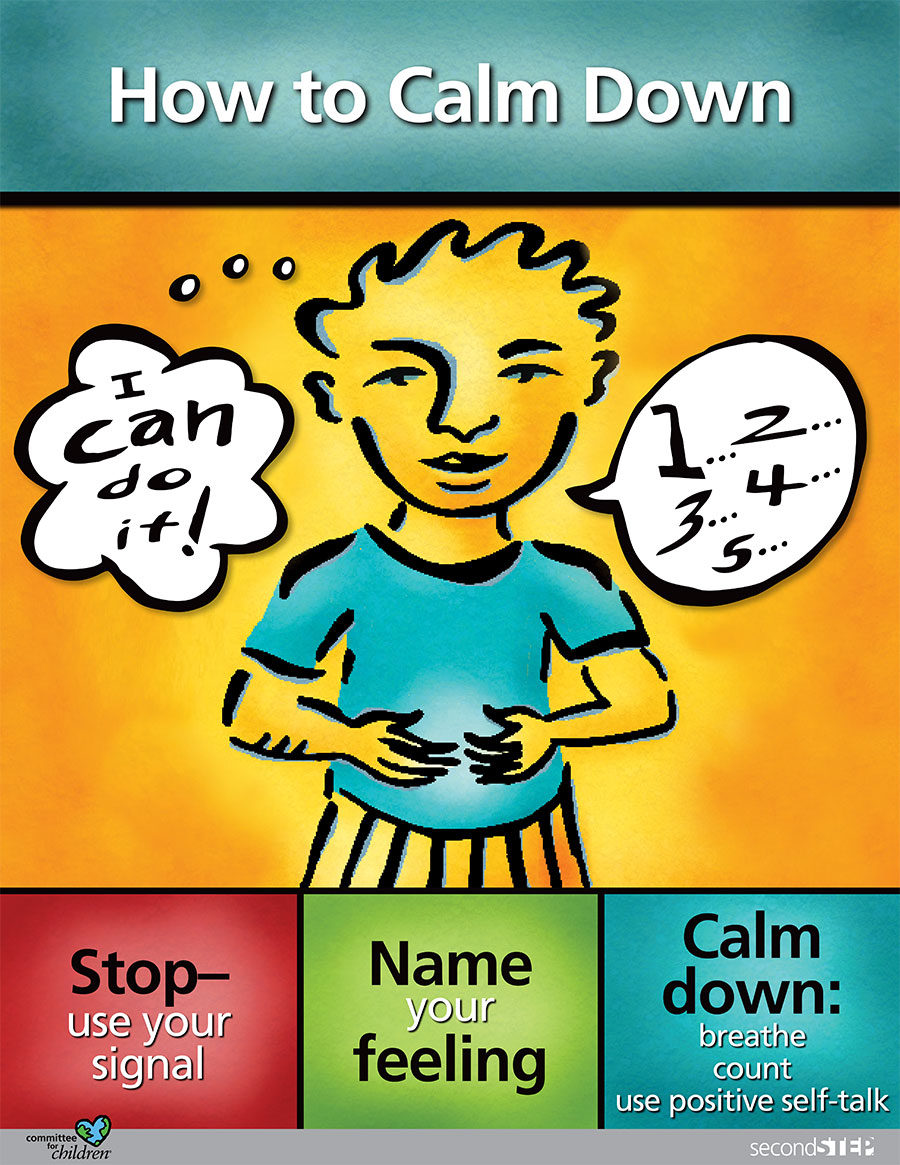

SEL curbs resistance, centering the regulation of negative and disruptive emotions. Common in the SEL program was forced counting and breathing, “calming” toys, muscle-relaxing games like “playing noodle” and going limp, stuffed animals, self-check posters, fidgets, and body socks. Teachers prompted children to use these until they were ready to talk. SEL asks youth to expel their anger and forget the arson all around them.

As Dr. Diane M. Hoffman argues, these practices presuppose emotions are “handled” through talking and if kept, will accumulate, boil over, and devastate. Hoffman rightly critiques that this culturally hegemonic view “sees [emotions] as internal, individual states that require active managerial control to be channeled in socially positive, healthy ways.”

In reality, social emotional learning is rarely about the emotions and experiences, but how the educator wants emotions to play out. After all, behaviors can be tracked as indicators that skills were taught—or absent—and the learner’s social emotional (in)competence can be determined.

In the classroom, educators tracked youths’ behaviors on point sheets fitted to three categories: respectful, responsible, and safe. Paraprofessionals determined points every thirty minutes, which they shared with youth. Catharine Sherman, a special education teacher, states, “The point sheet essentially is a self-management protocol. The goal is that kids rate their own behavior and build self-awareness and set management skills. We have a couple kids doing them on their own. It’s also obviously a means for us to track their progress in response to our interventions.”

You might walk in the room and hear “Aww that was so kind of you, Peter, saying good morning from your seat. You get ten bonus points.” And if a dispute emerged, “Whoever can apologize gets twenty bonus points!” Here, emotions are positioned as a pathway to achievement, not as the site of relational formation. These moments ask youth to cast aside their self-integrity and perform for authority, further alienating meaning from interactions.

These practices ameliorate the immediate without critically questioning what in the environment, in the community, in the teacher’s actions, in schooling, or most obvious, in social-emotional learning, made a youth feel uncomfortable, angry, hurt, scared, excluded. When rewards fail, as they will, practitioners turn to punishment, leveraging fear (for example, taking away points, or threating to call home).

Even amidst this domination, resistance emerges, further proof that building behaviors does not create community.

In my time at the public elementary school, the few humanizing relationships youth formed were surveilled, controlled, and severed as youth demanded dignity. Social emotional learning programs are being leveraged to increase this surveillance and control. The result is a wide-reaching, open-access invitation to emotionally disturb black and brown youth.

At the start of this article, I described two youth, policed in general education classrooms for expressing themselves. By the end of the school year, at ages six and eight, they were labeled “emotionally disturbed.” In their new classroom, chairs are bolted to the floor, desks face walls, and paraprofessionals hover with clipboards. They join Revon and Lemarr, and the teacher leads another Mindful Minute meditation on the rug.

I walk into the room. A student stands to greet me. “Ryan!” He says. He wraps me in a hug.

“Dauntay! Dauntay, sit back down. You need to be seated to earn points,” the teacher says.

“I’m just saying hi!” Dauntay says.

“You’re losing points,” the teacher says.

“I don’t care.” He responds.

“That’s not being respectful,” the teacher says.

“You’re making me mad.” Dauntay says.

“Then calm your body. Show me a safe body. You need a safe body to be a member of the community.” The teacher says.

To be clear, three of the five boys in this class are black, one is white. At the end of the day, teaching self-control is still about control.

Let us imagine a place where someone’s hurt, isolation, anger, or frustration calls their community and educators to invest more care and love in the relationship not less, to interrogate the environment with them, and to challenge the unjust.

When Dauntay left class, we built a relationship, as peers. We wandered the hallways of the school, sometimes quietly, sometimes talking about how the school treated him, sometimes talking about our lives and our homes, and sometimes our hopes. That is learning.